Lakes380 Wairarapa Field Trip January 2021

By Katie Brasell, PhD Candidate at Cawthron/UoA

This short but fruitful field trip was a week full of contrasts, both culturally and meteorologically, as you will see from the photos throughout this blog. I believe we can reduce the negativity often associated with contrasting thoughts, ideas, images and experiences by bringing them closer together – weaving them together to see the beauty they bring as one. Similarly, I have woven my contrasting knowledge of English (pretty good…) and te reo Māori (very limited) together to try and create a narrative for all to understand, hopefully learn from and grow to appreciate for the benefit of our shared future…

Wairarapa can be translated as glistening waters in te reo, this is what Haunui (the great-grandson of Kupe) saw after he scaled the Remutaka mountains and emerged into a grand valley that came down to meet a vast body of water – Ngā Whatu o te Ika a Māui (the eye of the fish of Māui), which we call Lake Wairarapa. Multiple bodies of water connect together to reach the Raukawakawa/Cook Strait through Te Waha o te Ika a Māui (the mouth of the fish) or the Lake Onoke mouth. Collectively, Lake Wairarapa, Lake Onoke and the surrounding wetlands and swamps are referred to as Wairarapa Moana – they are taonga of the tangata whenua and the focus of much scientific and cultural mahi (work) for Lakes380. Wairarapa Moana is one of three Lakes380 iwi rohe studies, meaning it has been prioritised in our work programme to demonstrate how we can weave the social, cultural and biophysical histories to create meaningful outputs. The Wairarapa Moana were also recently recognised (August 2020) as wetlands of international importance under the Ramsar convention – an exciting progression that will help support the need for greater protection and restoration efforts.

Image 1: Te Ika a Maui the North Island seen from a satellite, its tail stretching north and the southern tip its head. Ngā Whatu o te Ika a Maui is clearly visible as the light brown dot in the centre of the head, Wellington and the Wairarapa valley. Photo credit: ESA (http://www.esa.int/ESA_Multimedia/Images/2019/03/New_Zealand)

Image 2: View of Lake Wairarapa from the Remutaka (Rimutaka) Ranges, as Haunui might have seen it. Photo credit: David Johnson (Virtual New Zealand).

The Wairarapa is a special place for me. I grew up there, I played and swam in the Ruamāhanga river and paddled on Lake Wairarapa and Onoke (well, attempted to at least, despite the howling winds!). But this whenua still had much to teach me, and still does. I left this place as an 18-year-old, heading to university in Wellington, later moving north to work for DOC in Hamilton after completing my MSc. It wasn’t long before I felt the pull of home and the need to put my freshwater science skills to use where it meant something to me. Nearly two years of driving the gravel back roads of the Wairarapa for the Regional Council (GWRC), collecting water samples and monitoring algae growth, showed me more special places I had never been – it also showed me just how sick and degraded the awa (rivers) and moana (waterbodies) had become. The bed of the Ruamāhanga and Waipoua rivers are covered in potentially toxic algae each summer, when there are not enough high flow events to flush them off the rocks. The waterways of the eastern hills are laden with sediment from the bare slopes surrounding them. The lakes are a turbid brown from receiving the sediment and nutrients from an entire grand valley full of urban and agricultural development – including the diversion of the Ruamāhanga away from Lake Wairarapa and into Lake Onoke, so the flood waters could flush directly out to sea through the mouth that is now mechanically opened by the GWRC.

Image 3: Potentially toxic algae (Microcoleus autumnalis) blooming in the Waipoua River during the 2019 summer low flow conditions. Photo credit: Greater Wellington Regional Council.

Image 4: The aquatic weed Hornwort (Ceratophyllum demersum) grows abundantly in the wetlands and lakes surrounding Lake Wairarapa but is not present in the lake itself due to wind disturbance, nor Lake Onoke due to its saline conditions. Photo credit: Donald Cameron.

These sentiments of degradation and loss were echoed by manawhenua at Kohunui marae, who we met with in the sweltering 30°C heat for a wānanga on the first day of this Lakes380 field trip. We were humbled by the welcome we received and the openness of the whānau during this exchange. Kaumatua Aperahama ‘Abe’ Matenga and whaea Suzanne Murphy opened the proceedings, followed by Lee Kunui Flutey. They shared with us the history of their relationship with Wairarapa Moana, their current freshwater mahi and the challenges they still face. The Lakes380 team presented findings from biophysical data generated from Lake Wairarapa cores collected previously (which will be part of future Lakes380 communications), as well as a unique piece of work that our social science group, led by Charlotte Šunde, have been working on – the Wairarapa Moana Kete Pūrākau, an online digital storytelling portal created in response to MBIE’s vision Mātauranga policy. These exchanges created an opportunity for us all to discuss how we, collectively, might respond to the challenges of protecting and restoring Wairarapa Moana, while also empowering manawhenua. It was clear that seeing the stories of their moana, its loss, historical grievances and ongoing impacts of colonisation, articulated by whanau and other locals, brought up the mamae (hurt and sadness) that they still carry. Not forgetting that the wider community also has responsibilities as kaitiaki, and it is through shared knowledge and experiences that we can all come together to manaaki (care for, protect, respect) Wairarapa Moana.

There was much shared learning from the day’s kōrero and I felt a sense of purpose to our mahi in empowering these kaitiaki to help heal the whenua and restore waiora (health of the water) and in doing so, uphold the mana of the land and people. Through Lakes380, the knowledge and understanding we bring about the environmental origins of things, as kaumatua Abe put it, and what that can tell us about the past, present and future, is precious to many. Although I felt the mamae resonating with me from the day’s discussions, I took great pride in being part of Lakes380 and our contributions towards this ongoing mahi tahi (collaboration).

Image 5: Tuesdays wānanga at Kohunui Marae near Pirinoa and Lake Onoke. Some great kōrero were shared by both parties, weaving knowledge new and old, both science and tikanga, together to better understand the environmental history of Wairarapa Moana. Front from left: Solitce Morrison, Lee Kunui Flutey, Aperahama Matenga, Marcus Vandergoes, Charlotte Šunde, Maralee Allen, Teresa Aporo, Suzanne Murphy, Bruce Foster. Back from left: Myself (Katie Brasell), Heni Unwin, Sean Waters, Simon Te Maari, Andrew Rees, Alberta Aiono, Arial Te Maari. Attendees not pictured: Rawiri Smith, Jay Pu’e, Matui Te Maari.

Image 6: Teresa Aporo reaches down to feel the texture and take in the smell of lake sediment from nearby Lake Pounui – texture and smell are important mātauranga cultural health indicator methods, as well as in western science. Grain size and organic matter (carbon) content can indicate where sediments have come from and the amount of primary productivity at the time of deposition.

The intense heat continued for the second day of our trip, where we gathered on the shore of Lake Onoke, in the township of Lake Ferry. We were joined by folks from GWRC and DOC as well as interns from GNS Science, students from Wairarapa Land Based Training and our friends from Kohunui Marae. I was also pleased to invite my Dad (a local farmer and sustainability champion) down to join us at the lake – I’m continually inspired by his willingness break the mould of traditional rural farming attitudes and show that environmental and social benefits can go hand in hand with productive farming.

With the sun glaring down on us, kaumatua Abe opened with a karakia followed by some insightful korero from matua Rawiri Smith – always a wealth of knowledge when it comes to Wairarapa history. Marcus, Andrew and Charlotte spoke to the group, all huddled in the shrinking area of shade, about why and how we collect our sample/data, before heading out to do some on-lake demonstrations. The demo cores collected close to the river and lake mouth were mostly filled with sand due to the high flows in this area of the lake, which don’t accumulate the fine sediments that we usually find in our cores – instead the heavier particles that settle out quicker are what is deposited in this part of the lake. We later took cores from the western side of Onoke where the flow was much less, however the extremely sticky clay sediments here made for difficult coring.

Image 7: Marcus Vandergoes (GNS) and Andrew Rees (VUW) speaks to the group during the Knowledge Sharing Day on the shore of Lake Onoke, during the intense 30°C heat.

Image 8: Marcus and Sean Waters (Cawthron) fit the Lakes380 coring boat, Kea, with an outboard motor, while Alton Perrie (GWRC) sets fishing nets with Land Based Training students in the background to see what eels and fish are present.

Image 9: Core sample collected from the high flow channel near the Lake Onoke mouth. This is mostly comprised of sands, but a small segment of sticky clays is visible at the base of the core.

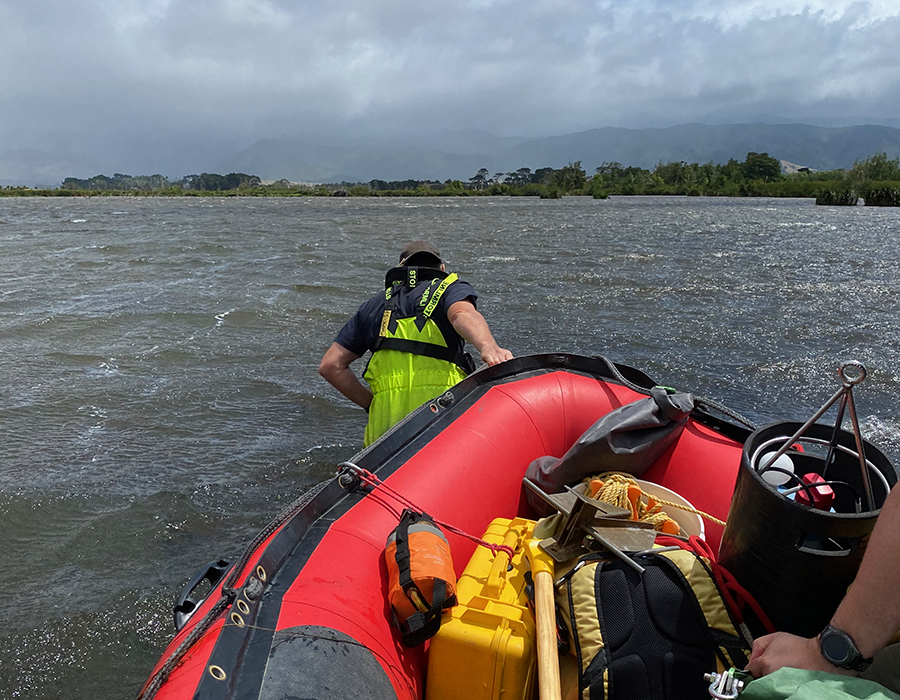

After two days of baking heat, our third day could not have been more different! High winds and a temperature high of 14°C reminded me of one important component of our research – understanding climate change, the impacts it has had and what it means for the future of our lakes. As we pulled up at Turner’s Lagoon, just off Western Lake Rd, we quickly ascertained we would not be coring or even launching the boat in the barely knee-deep water, not to mention the wind! Continuing on to Barton’s Lagoon that adjoins the northern edge of Lake Wairarapa, we eventually found our way through the over-grown tracks to a launching site – hoping for more suitable coring conditions. The chokingly abundant aquatic weed, Hornwort, prevented us from using the outboard motor so we were left to wade and paddle the boat out to our coring site against the howling wind. Despite the buckets loads of surface spray flying at us and the mere 0.9 m of water depth, the coring came relatively easily, and we finally had our second lake sampled for the trip.

Image 10: The infamous howling winds of Wairarapa were on form as we prepared to sample Barton’s Lagoon.

Image 11: Barton’s Lagoon with some ominous clouds looming…

Image 12: Sean tows us out to deeper waters at Barton’s Lagoon, against the wild weather. No motorised help here due to the thick beds of Hornwort in the lake.

Our one and only two-lake day rounded off the trip. Starting with Rototawai, a small lake mostly used for duck shooting on a farm near Kahutara. The day brought much calmer conditions that made for pleasant sampling. A noticeable abundance of green algal colonies in the water column and bright green scum at the water’s edge indicated high primary productivity – and also made for some laborious water filtering back on shore… From here we headed 10 kms south to sample Matthew’s Lagoon, next to the aptly named Boggy Pond – these two waterbodies make up the largest of the Wairarapa Moana wetland complexes. This brought our short but eventful week of sampling to an end. Some would wonder why we are bothering to sample these ‘muddy puddles’ that many would not consider lakes. But it is hoped we can find evidence of the many large-scale landscape changes that have occurred in the Wairarapa over the past 1,000 – 5,000 years to help build a clearer picture. Previous coring data indicated Lake Wairarapa was a saltwater embayment completely open to the sea around 5,000 years ago and multiple earthquakes have caused landscape shifts in different areas of the lower valley since then.

Image 13: The team ready to launch at Rototawai, joined by Darian Kissick, an Environmental Monitoring Officer at GWRC.

Image 14: Spherical algal colonies (possibly of the Volvox genus) visible in the water samples during filter back on shore – Chlorophyl-a levels will no doubt be high!

Image 15: Launching site at Matthew’s Lagoon, surrounded by tall raupō (Typha orientalis) and some remaining exotic willow trees that were once encouraged to grow but are now less favoured in comparison to native wetland species.

Although it was a short trip, with a total of four lakes sampled at a more leisurely pace than normal, something about doing the mahi on my own home turf kept me switched on all day. I finished the week quite exhausted but very fulfulled. It was a privilege to be part of the team and to continue to connect with my whenua, moana and awa in new and exciting ways.

Thanks to Claire Shepherd (GNS) and Soltice Morrison (BLAKE intern at GNS) for their support during the field trip and the wider team of people who came along to learn or lend a hand – Darian, Alton, James & Ashley (GWRC) and Gracie, Robyn, Jonti & Peter (GNS). As I mentioned earlier you can explore the Wairarapa Moana Kete Pūrākau for yourself here: https://www.lakestoriesnz.org. The Wairarapa Moana project also have their own website or this great book. There are also some quick links to general history of Māori people in the Wairarapa from GWRC and the Ministry of Education has a helpful resource of myths, legends and contemporary stories, such as the story of Māui fishing up the North Island.